Mountaintop Removal Cuts Through Southern Forests

New maps from SeeSouthernForests.org show the scale of forest loss from surface mining in Appalachia.

Mountaintop removal has become an increasingly contentious issue over the past several decades, particularly in the southern United States. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that by the end of 2010, 1.4 million acres of Appalachian forests will have been disturbed or cleared by http://www.epa.gov/region3/mtntop/eis2005.htm)">mountaintop removal, an area larger than Delaware. And a recent decision by the Army Corp of Engineers has suspended fast-track permitting for mountaintop removal operations in Appalachia. But why is this mining practice so controversial? Where is it taking place? And what impact is it having on forests?

What is Mountaintop Removal?

Mountaintop removal is a surface mining technique in which explosives are used to remove large areas of mountaintops in order to access underlying coal seams. Before explosives can be used, however, the land must be cleared of all vegetation, including trees and topsoil. After the vegetation is removed, excess rock, debris, and mining byproducts are pushed into adjacent valleys, where they bury existing streams. Coal companies employ this mining method because it allows for almost complete recovery of coal seams and requires fewer workers than conventional mining. In the United States, mountaintop removal is concentrated in the central Appalachia, an area that includes southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, southwest Virginia, and eastern Tennessee. This area produces 33% of all U.S. coal, 40% of which comes from surface mining.

The Impact of Mountaintop Removal

Surface mining has played an important role in local economic development in central Appalachia, generating jobs and hundreds of millions of dollars in state revenue across the region every year. However, the environmental impacts of mountaintop removal are severe. Mountaintop removal is a disruptive practice that requires large areas of land and associated forests to be cleared.

Inevitably, this scale of forest loss has already had a negative impact on carbon sequestration, water quality, and other forest-dependent ecosystem services. Furthermore, despite required reclamation efforts, cleared areas rarely return to their original level of biodiversity, as grasses and other non-woody vegetation tend to reclaim these areas instead of the woody growth that existed before the area was cleared. Carbon sequestration – the ability of forests to absorb carbon dioxide from the air – also significantly declines after trees are cleared. In fact, many “reclaimed areas” show little or no regrowth of woody vegetation and thus minimal carbon storage even after 15 years. Water quality also declines as a result of dumping mining “spoil” in existing streams. According to the U.S. EPA, since 1992, nearly 2,000 miles of Appalachian streams have been buried by mining refuse. Furthermore, nine out of every ten streams downstream from surface mining operations have been found to be polluted.

The Scale of Mountaintop Removal

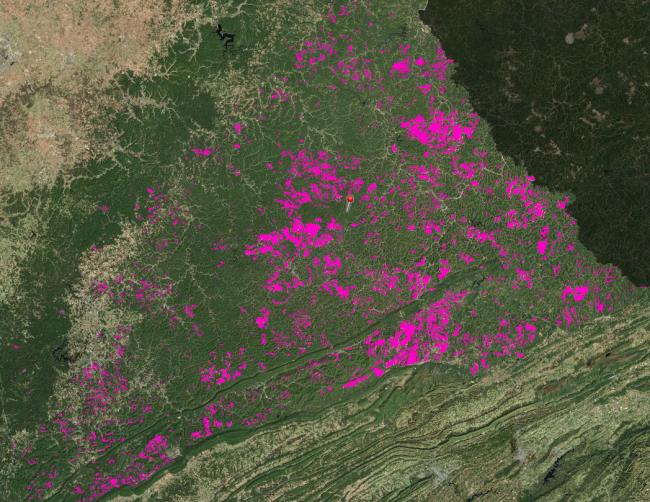

But at what scale is mountaintop removal actually occurring? Until recently, information about the geographic extent of mountaintop mining was scarce. Today, however, using maps produced by Ross Geredien (in partnership with Appalachian Voices) and hosted on SeeSouthernForests.org, users can now map forest loss from surface mining to see exactly where mountaintop removal is occurring, clearly illustrating the significant impact this mining practice has had on the natural landscape. Furthermore, the EPA is making a more concerted effort to measure and track the impact of mountaintop removal after announcing that it is a high priority of their administration and their administrator, Lisa P. Jackson, to reduce the substantial environmental and human health consequences of surface coal mining in Appalachia, and minimize further impairment of already compromised watersheds.

Image from SeeSouthernForests.org showing forest loss (in pink) due to mountaintop removal in Eastern Kentucky. View map here (Select “Show Additional Map Data”)

Image from SeeSouthernForests.org showing forest loss (in pink) due to mountaintop removal in Eastern Kentucky. View map here (Select “Show Additional Map Data”)

High resolution satellite image of a mountaintop removal mining site west of Vest, Kentucky.

High resolution satellite image of a mountaintop removal mining site west of Vest, Kentucky.Scientists Speak Out

In January 2010, thirteen scientists from various respected U.S. universities published an article in Science magazine discussing the significant environmental and health consequences of mountaintop mining / removal with valley fills (MTM/VF)1. In a scientific survey of 78 MTM/VF streams, they found that 73 streams had selenium concentrations greater than the threshold for toxic bioaccumulation. As a result of exposure to high selenium levels, fish in the affected streams lost their ability to reproduce. Furthermore, numerous state advisories were issued to discourage people from eating fish from MTM/VF-affected water, due to the potential health risks.

The scientists discussed additional potential human health impacts of MTM/VF, particularly due to airborne, hazardous dust generated by mining operations. This dust has led to elevated levels of adult hospitalizations for chronic pulmonary disorders and hypertension; higher rates of mortality; lung cancer; and chronic heart, lung, and kidney disease for individuals living in mining areas .

The Science article also discussed the lack of strong U.S. policy to effectively regulate MTM/VF practices, and expressed concern that mining permits are issued without consideration of the long-term and irreversible environmental and health impacts.

Finally, they concluded, “Considering environmental impacts of MTM/VF, in combination with evidence that the health of people living in surface-mining regions of the central Appalachians is compromised by mining activities, we conclude that MTM/VF permits should not be granted unless new methods can be subjected to rigorous peer review and shown to remedy these problems” (Science, Vol 327, January 8, 2010).

EPA Action

In response to the article and interest in reducing the environmental and health impacts of surface mining, EPA released a guidance document on April 1, 2010 designed to improve its review of Appalachian surface coal mining operations under the Clean Water Act, National Environmental Policy Act, and the Environmental Justice Executive Order. This guidance document outlines concerns about the environmental and health impacts of surface mining, focusing on the negative impacts of mining operations on downstream water quality.

Furthermore, it implies that the EPA may block new mining permits if the operation is predicted to pollute water above a certain level2. What impact will this new requirement have on new surface mining permits? EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson told reporters, “Minimizing the number of valley fills is a very, very key factor. You’re talking about no or very few valley fills that are going to be able to meet standards like this.”

Learn More at SeeSouthernForests.org

While recent actions by the scientific community and EPA have encouraged limiting mountaintop removal, it is still too soon to assess what impact these actions will have on curtailing mountain top mining over the long term. However, actions by mining companies and EPA in the next few months should lend some insight into the future of mountaintop removal mining practices in the United States. Visit SeeSouthernForests.org for the most recent news on this issue as it’s released.

1. M. A. Palmer, E. S. Bernhardt, W. H. Schlesinger, K. N. Eshleman, E. Foufoula-Georgiou, M. S. Hendryx, A. D. Lemly, G. E. Likens, O. L. Loucks, M. E. Power, P. S. White, P. R. Wilcock. Mountaintop Mining Consequences. Science, 2010; 327 (5962): 148 DOI: 10.1126/science.1180543.

2. Specifically, if the mining operation causes water conductivity – the measure of the presence of many harmful pollutants, such as chlorides, sulfides and dissolved solids – of more than 500 microsiemens per centimeter.