History

To better view the horizon of southern forests and their ecosystem services, it is helpful to briefly look at the landscape of the past. The history of these forests is one of dynamic change. Since the end of the last ice age, natural disturbances and human activities have continually shaped southern forests. Changes in climate affected species composition and distribution. Hurricanes, tornadoes, and other natural events created periodic forest clearings. Frequent low-intensity fires set by Native Americans created openings and influenced the dynamics of fire-dependent forest ecosystems.

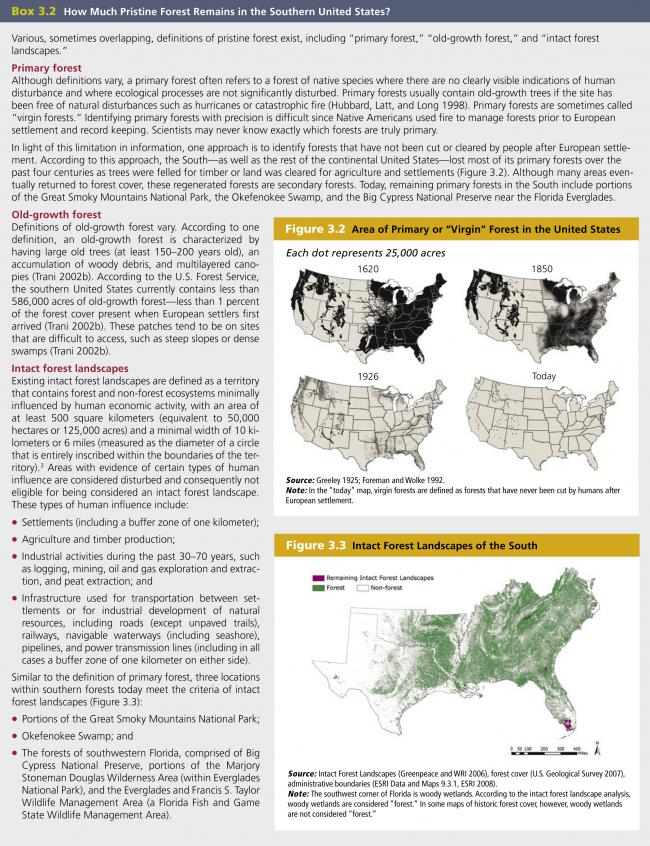

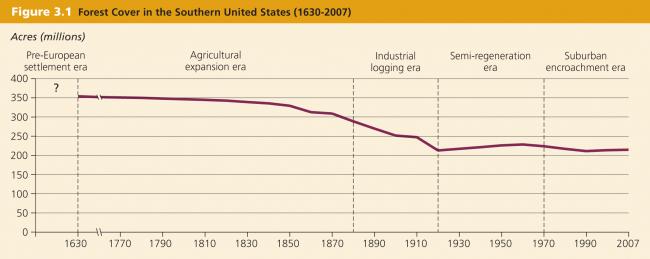

Over the past 400 years, activities such as agriculture, timber extraction, and settlement by European colonists and their descendents have been leading sources of human-induced change in southern forests. One indicator of this change is forest extent. Although information is limited (Box 3.1), some estimates suggest that forests covered more than 350 million acres throughout the South in the early 1600s.1 During the subsequent four centuries, more than 99 percent of these acres were cut at one time or another; very little pristine or primary southern forest remains (Box 3.2).2 Demonstrating the renewability and resiliency of forests, much of the land regenerated over time as secondary forest. However, approximately 40 percent of estimated pre-European settlement forest acreage has been converted to other uses.3

Source: Total forest extent from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data, and in Smith et al. 2009.

Note: The time boundaries of each era are estimates. The drivers of change that defined each era often overlapped in time.

Source: Total forest extent from U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data, and in Smith et al. 2009.

Note: The time boundaries of each era are estimates. The drivers of change that defined each era often overlapped in time.A few caveats are worth noting. First, the drivers of change in these eras often overlap and interact. For instance, a forest may initially be harvested for timber and subsequently converted into farmland. Second, the start of one era does not necessarily mean that the previous era’s leading driver of change ceased having impact. For example, agriculture continued to expand during the industrial logging era. Thus, these eras are simplifications of a more complex historical reality. Third, the drivers of change vary by the degree of permanence of their impacts. For example, after a timber harvest, a forest will regenerate; forests are renewable. Agriculture may suppress forest regeneration for a time, but forests will return if farming ceases. Urban and suburban settlements, on the other hand, entail more long-term forest change.

-

Wear, D.N. and J.G. Greis. 2002b. The Southern Forest Resource Assessment: Summary Report. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-54. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. ↩

-

Trani, Margaret K. 2002b. “Terrestrial Ecosystems.” In Wear, David N., and John G. Greis, eds. Southern Forest Resource Assessment. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-53. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. ↩

-

Wear, D.N. and J.G. Greis. 2002b. The Southern Forest Resource Assessment: Summary Report. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-54. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. ↩