“Working Forests” – How Land Protection Can Save and Even Make Money

By John Talberth

By John Talberth

Public support remains high for land conservation, even in the challenging state of today’s economy. Traditional conservation strategies rely on public institutions to purchase land from private owners and protect these areas by forming parks, wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, and other open spaces. However, since it is becoming increasingly difficult to add conservation expenses to public budgets, states, counties and municipalities can benefit from creating “working forests” that save and even make them money.

The World Resources Institute investigates working forest land conservation strategies in Forests at Work: A New Model for Local Land Protection. This issue brief provides an overview of how public land, including forestland, can be “put to work” to earn revenue from one or more ecosystem service market opportunities. Working forest revenue sources include sustainable timber production, recreation and hunting fees, and – to the extent that management activities enhance environmental quality – payments for carbon sequestration, endangered species habitats, and/or water quality.

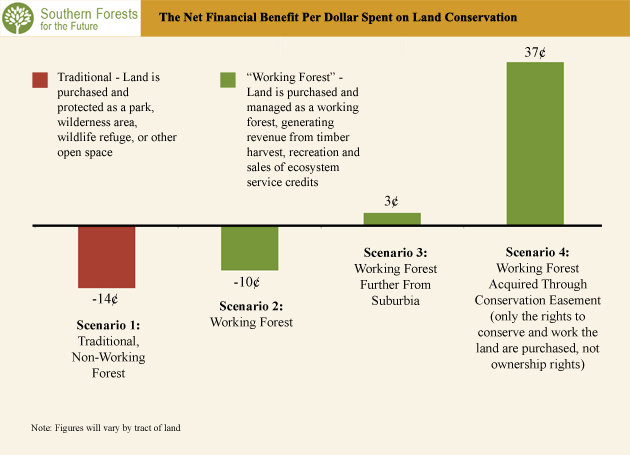

The figure below depicts the net financial impact of four working forest protection scenarios, based on data and projections for a suburban county in North Carolina:

- Scenario 1: the traditional approach, where a county or municipality purchases land from willing sellers and protects the land as a county park or other open space designation that has minimal revenue-generating opportunities. For every $1.00 spent, the county receives $.86 back in the form of financial benefits from sources such as higher property tax collections on surrounding lands and the avoided costs of not providing community services and infrastructure if the parcel had been developed into a residential subdivision.

- Scenario 2: a new model for suburban areas where the locality purchases land but manages it as a working forest. In this scenario, revenues from timber harvest, recreation and sales of ecosystem service credits – such as those for water quality, wildlife habitat and carbon – are built into the management plan. Under this scenario, for every $1.00 spent acquiring the land, the county receives $.90 back.

- Scenario 3: the same working forest model as Scenario 3, but the parcel acquired is a bit further away from the suburbs, making land acquisition costs a bit lower. Under this scenario, for every $1.00 spent on the acquisition, the working forest model returns $1.03. In other words, this working forest earns more than it costs.

- Scenario 4: a model for acquiring land through a conservation easement rather than buying the land outright. Under an easement purchase, the county does not pay the full market price for the land because ownership rights are not acquired. These rights remain with the landowner. The county, however, retains rights to receive revenue from timber and other ecosystem services. Under this scenario, for every $1.00 spent, the county receives $1.37 in financial return.

Gaining revenue from protected forest ecosystems that are managed as working forests is possible and beneficial. The purchase of conservation easements to enable the management of working forests instead of purchasing land for parks can reduce costs and increase revenues to local government. While the financial result of different types of land acquisitions in different locales will vary, this analysis demonstrates why counties and municipal governments interested in getting the most “bang for the buck” out of their conservation dollars should consider a working forest acquisition approach, rather than a more traditional land conservation strategy.

(Click to enlarge)

(Click to enlarge)